In death, as in life, Rabbani fails to bring peace

Only in Afghanistan. Only in broken, blighted, beguiling, and wholly implausible Afghanistan can such rich ironies coexist.

On International Peace Day -- a UN-sanctioned affair overlooked in most countries, but for some reason enthusiastically observed in Afghanistan – ordinary Afghans, we are told, are mourning a setback for peace with the killing of Burhanuddin Rabbani.

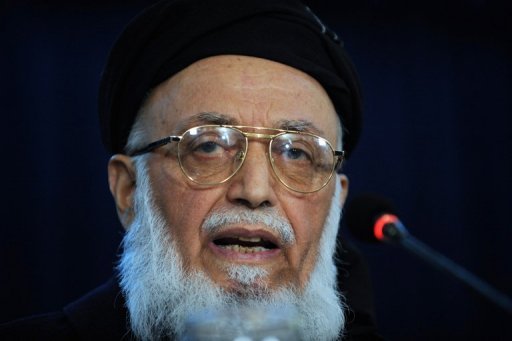

Rabbani, a sclerotic former Afghan president who oversaw the brutal, fractious 1990s civil war that killed thousands, was the chief of Afghanistan’s High Peace Council.

The man largely responsible for reducing the country to such a state of shambles that ordinary Afghans actually welcomed the 1996 Taliban takeover was the point-man entrusted with the national reconciliation mission.

The Cold War CIA-funded warlord who wasn’t above accepting Russian arms during his Northern Alliance’s desperate war against the Taliban was charged with – hey, peace-brokering with his arch enemies.

The silver-bearded, impeccably-outfitted Islamist professor-politician whose political rise in the 1970s heralded the effective demise of any secular discourse in modern Afghan politics was, we’re told, a moderate Islamist - whatever that means and however that’s defined.

The septuagenarian former-statesman who refused to give up his slot in what was meant to be a rotating presidency in the 1990s, vied for power at every opportune moment, and turned up like a bad penny at every crucial meeting, jirga, or council in modern Afghan history (to the consternation of most right-thinking Afghans), is no more.

And with his passing, we’re being told, any hopes of a peaceful political transition in a country that hasn’t seen one in almost seven decades – if not more – is as dead as Rabbani.

Whodunit? Speak Mister Mujahid!

Even in death, the ironies are still coming alive.

By early Wednesday, Reuters was quoting our now familiar Taliban spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, as claiming the attack.

This seemed fairly plausible since Rabbani was killed during a pre-arranged meeting with Taliban representatives as part of his High Peace Council initiatives.

Mister Mujahid – as I like to call him in a country brimming with mujahids – is believed to be linked to the Haqqani branch of the Taliban and can sometimes grandiosely spike death tolls and claim attacks his group never committed. In the news business, we have to take recourse to the arsenal of doubtspeak at our disposal – alleged, reported, purported, that sort of thing - when reporting Mister Mujahid’s claims.

But by mid-Wednesday, we realized that even the Taliban was not particularly keen on claiming this one.

“Because our information on this is yet to be completed our stand is that we can't comment on this at all. And the media that, quoting us reporting that we have taken responsibility all their reports are baseless and once again we say that at the moment we don't want to comment on this.”

That’s the English translation from Pashtu supplied by the redoubtable Kabul Pressistan, my favorite Afghan journalists’ resource.

Note: They aren’t denying it. They’re just not commenting on it.

Smooth.

Talking to the Taliban: With us or against us

Then we come to the business of what Rabbani’s death means for the future of the peace negotiations with the Taliban.

I’ve looked around the pundit posts and the verdict is clear: Rabbani’s demise is bad news for the peace talks with the Taliban.

I really don’t know. When it comes to this “talking with the Taliban” business, I have several friends – old Afghan-hands, experts who are far smarter and know Afghanistan much better than me, whose opinions I respect – sold on this path.

When I’m in reporter mode, when I worship at the temple of objectivity, decades of sound journalistic training kick in and their argument seems perfectly cogent and compelling.

But when I’m in blogger mode, and I’m permitted some honest opinion, I wonder what are these people smoking?

See, when it comes to Afghanistan, I myself am riddled with richly ironic juxtapositions.

What peace negotiations are we talking about when the list of Taliban assassinations over the past few months reads like a who’s who of senior Afghan figures: General Daud Daud, General Abdul Rahman Sayedkhili, former Uruzgan governor and Karzai aide Jan Muhammad Khan, and Karzai’s own half-brother Ahmad Walid Karzai - to name just the top-notch?

All not quite quiet on the Tajik front

In the new, post-Rabbani world, analysts are noting the tough intransigent talk from senior Tajik figures.

In her blog, Kate Clark from the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network notes that opposition politician Dr. Abdullah Abdullah has called the Taliban, “people who don’t believe in any humanity,” while Balkh governor Nur Atta Muhammad called them “wild beasts”.

The Tajiks, we’re being told, are especially roiled up with the slaying of one of their own.

Start the discourse on the effects of this assassination on the delicate ethnic fabric of Afghan society.

So the question is, with Rabbani's death, will the Tajiks be slapped with a "peace-spoiler" tag for not enthusiastically jumping on the negotiations with the Taliban bandwagon?

Well, I’m not sure how many Tajiks actually felt reassured by Rabbani’s presence in the High Peace Council in the first place.

This entire Taliban-talking business has been the initiative of a Pashtun president who suffers from a fairly common head-of-state malaise of doing what it takes to stay in power.

For the Tajiks, putting one of Afghanistan’s most expedient politicians in the top High Peace Council spot didn’t exactly transform the Taliban-talking pill into candy.

Candy is dandy, to quote Ogden Nash. But in Islamic Afghanistan, it’s conflict – not liquor – that’s quicker.

That multi-million dollar peace and reconciliation dream looks further than it ever was.

Of course Washington isn’t looking – they have a troop pullout plan and an election looming. Islamabad is rubbing its neighborly hands gleefully. As for Tehran and New Delhi, well, that’s another blog post.

May be in death Rabbani will finally provide the clarity the dignified, old, foxy soul never did in life. Peace, as we see it, in Afghanistan is not on the cards. I leave you to count on Mullah Omar and Sirajuddin Haqqani’s good intentions.

2 Comments

Post new comment