Another video, another Christmas in captivity?

For nearly 18 months, Private Bowe Bergdahl, the only known US soldier to be held captive by the Taliban, has been held hostage somewhere in the wilds between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

We’ve seen glimpses of the captured US soldier from time to time – sometimes bearded, sometimes not, sometimes pleading for his life – in video footage released by the Taliban.

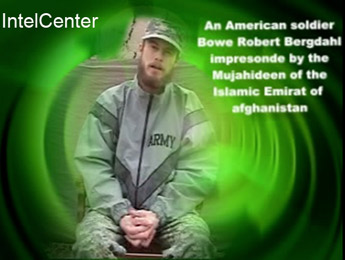

The latest footage emerged earlier this week, when the Intel Center, a US-based group that monitors militant propaganda, spotted Bergdahl in a video clip.

Dressed in a tan kameez - or traditional Pashtun shirt - with a distinctive bruise on his left cheek, Bergdahl stands next to a man variously known as Maulawi Sangin or Mullah Sangeen Zadran, a senior commander in the Haqqani network in Paktika province.

Bergdahl was captured on June 30, 2009 in Paktika, an eastern Afghan province that borders Pakistan.

It’s not clear when the latest footage was filmed. Judging from the background and Bergdahl’s open-necked kameez without the de rigueur patou - or enveloping woollen shawl - it does not look like the video was shot in winter.

While Bergdahl’s parents have declined to speak with reporters throughout the ordeal, a US military official told reporters in Kabul that Bob and Jani Bergdahl had confirmed that the man in the latest video was their son.

But if every militant video tells a strictly scripted story, the unwritten “backstory” of jihadist videos is sometimes more enlightening – and frightening.

Over the past few years, we’ve been inundated by militant audio and video messages of varying quality and production standards put out by various jihadist groups.

What’s striking about the four videos of Bergdahl however, is the different jihadist media arms that have produced and released the clips. In many ways, it reflects the complex organizational structure of the Afghan insurgency and the fluid links between various groups and commanders that fall under the broad Taliban rubric.

Jihadist propaganda – including videos, audio messages and statements – are produced by what experts call “media production groups,” which have a distinctive insignia and cover a defined corner of the vast global jihadist network.

Al Qaeda seems to be on top of the game with every geographic faction boasting its own media wing.

As-Sahab (The Cloud in Arabic), for example, covers what experts call “al Qaeda central command” – or the senior al Qaeda leaders, such as Osama bi Laden and Ayman al Zawahiri, based in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region.

The Somali al Shabaab media arm is called al-Kataib (The Brigade in Arabic). Al Malahim is the propaganda arm for al Qaeda in the Arabic Peninsular (AQAP) while al Andalus is the media center for al Qaeda’s North Africa branch, also known as al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

“Only the Taliban in Afghanistan does not have one single production group doing videos for the Taliban, there are at least five or six groups all putting out videos,” notes IntelCenter chief Ben Venzke.

An IntelCenter “link analysis chart” on the Bergdahl case details the different media arms that have released videos over the past 18 months.

The first video featuring Bergdahl, which was released on July 18, 2009, just weeks after his capture, was produced by the Media Center of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The second, released five months later on Christmas Day, was produced by the al Emarah Jihadi Studio. The latest video footage comes to us from Manba al Jihad.

Interestingly, the Dec. 7, 2010 video, unlike the three previous ones, is not dedicated exclusively to Bergdahl. Instead, the Idaho native and prize Taliban catch appears briefly, along with Mullah Sangeen Zadran, in the 45-minute tape.

Zadran’s presence suggests that Bergdahl is or was being held by the Haqqani network, led by Jalaluddin Haqqani and run by his son, Sirajuddin Haqqani. The father-son team operates out of Pakistan’s tribal Waziristan region.

US military officials decline to comment on whether they believe Bergdahl is currently being held in Afghan or Pakistani territory.

A number of hostages, such as the New York Times’ David Rohde, were captured in Afghanistan and later moved over the border into the Pakistani tribal areas, where militants enjoy considerable freedom.

Freedom though continues to evade Bergdahl as he looks set to spend another Christmas in captivity.

For criminal or militant groups, hostages sometimes hold the promise of big buck ransom payments. That tends to be the case when hostages happen to be European citizens, with the possible exception of Britain.

No government acknowledges it, yet everyone knows millions of dollars of ransom payments are forked out by European governments.

In Bergdahl’s case though, the US is known to refuse ransom payments, which makes the US soldier a prime propaganda weapon for his captors. Expect to see or hear more of this hapless captured soldier in the New Year.

0 Comments

Post new comment